Excerpts from the book “Art in Dialogue with Nature”

When Antoni Gaudí took over as main architect of the Sagrada Familia in 1883, his feelings towards Christianity– not unlike those of Daniel Defoe’s fictional hero Robinson Crusoe – were rather ambiguous. His scepticism notwithstanding, he went on to create the monumental stone bible that is now a staple landmark of Barcelona. Inspired by his dedicated study of liturgy and the spiritual dialogue between art and nature, Gaudi finally found his faith as an architect. Similarly, Robinson on his lonely island developed a relationship with God through his conversations with nature.

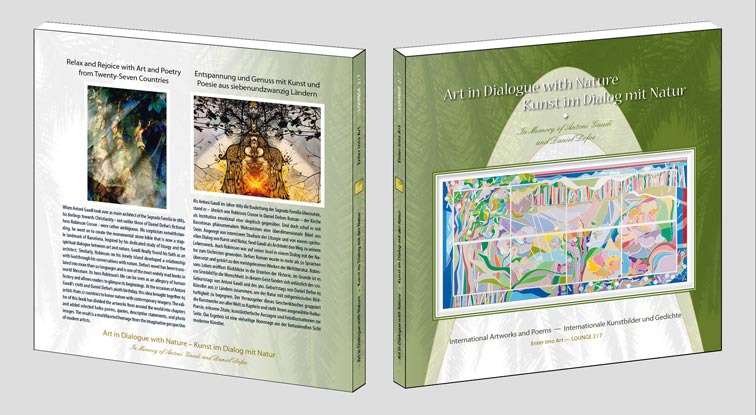

Defoe’s novel has been translated into more than 50 languages and is one of the most widely read books in world literature. Its hero Robinson’s life can be seen as an allegory of human history and allows readers to glimpse its beginnings. At the occasion of Antoni Gaudí’s 170th and Daniel Defoe’s 360th birthday, this idea brought together 65 artists from 27 countries to honor nature with contemporary imagery. The editor of this book has divided the artworks from around the world into chapters and added selected haiku poems, quotes, descriptive statements, and photo images. The result is a multifaceted homage from the imaginative perspective of modern artists.

The text and the poems in this post are excerpts from the book “Art in Dialogue with Nature”.

In Memory of Antoni Gaudí and Daniel Defoe

The main entrance of the Nativity façade on the Eastern side of the Sagrada Familia resembles the mouth of a gigantic cave, and features several likenesses of St. Joseph, the patron saint and helmsman of the family, always poised to steer the ship through the most perilous waters. Gaudí wanted the entrance colorful like the originally colored temples of Ancient Greece. (These had originally been wooden structures.). A green cypress made of glass symbolizes nature, his most respected teacher. The monochromatic sculptures at the entrance of the Passion façade seem rough and edgy in comparison. The negative depiction of the characters in the Passion of Christ appearing as “savages” can be compared with the cannibals on Robinson’s island.

Upon entering Barcelona’s church temple, visitors are overwhelmed by gentle rainbow-colored light flooding in through the high gothic windows. Typically, Gaudí’s crucial finding that paraboloid structures with tilted pillars could withstand the downward pressure of large vaults, was taken from nature itself: His model was the eucalyptus tree. At a height of 172,50 m/565 ft, the spire dedicated to Jesus Christ is scheduled to tower over Barcelona from/ be completed in 2026, respectfully kept 50 cm/1.5 ft lower than Montjuic, the local mountain erected by God Himself.

Near the mountain at the quay, the Columbus Monument stretches towards the sky. After discovering America, Columbus was granted an audience at the Royal Palace of Spain located in the historical old town, and Barcelona went on to become a gate to the world. Later, many emigrants returned from America with new-found wealth and began to hire Gaudí, granting him increasing levels of artistic freedom. The resulting residences of the Indianos clearly stand out among the drab expanses of monotonous hotel buildings on the Costa Brava. Inspired by the tropics, the famous coast sports the most gorgeous gardens: at places like Cap Roig in Calella de Palafrugell, Jardines de Santa Clotilde in Lloret de Mar, and the botanical gardens Marimurtra and Pinya de Rosa in Blanes, visitors can get a sense of Robinson’s surroundings on the island and enter a state of mind likely to produce poetry like the haiku poems featured in this book.

Conversing with Nature

Seafaring played a major role in both Defoe’s und Gaudí’s lives. At a height of 50 m/165 ft, the shape of the Columbus Monument faintly resembles the thin pinnacles of the Sagrada Familia covered with Trencadís mosaics – one of the hallmark features of Gaudí’s work. In its enormous, light-flooded verticality, the church seems to hover between heaven and earth. Robinson, too, was convinced that “some secret power, who formed the earth and sea, the air and sky” existed, and wondered: “who is that?” His friend Friday objected: “If God much strong, much might as the Devil, why God no kill the Devil, so make him no more do wicked? While his life was certainly blessed with adventure, Robinson also experienced the pangs of longing for the comfort of a family implied in Gaudí’s cathedral. In some Austrian robinsonades, Friday appears as a woman.

Surrounded by coconut, orange, lime and lemon trees, Robinson did own something like a “country mansion” and a “seaside villa” but becoming stranded on a lonely island was not his idea of reaching paradise. On his “Island of Despair”, he had no hoe, no shovel, no pots, no wheelbarrow, and no basket, having to improvise and work hard simply to survive. After he had made a fortune trading slaves in Brazil, nature had taught him that the good things in this world have no value if we cannot use them, and that freedom is the greatest good of man.

Robinson’s story was inspired by the life of the Scottish privateer Alexander Selkirk who had been marooned on the Pacific island now called Isla Robinson Crusoe (Chile) in 1704. Many years later, in 2010, reality mimicked the events of the novel when an earthquake struck and triggered a tsunami there, destroying almost every home on the island, and claiming several lives. As the wave rapidly rolled towards the coast, a twelve-year-old girl rang the warning bell, saving many of her neighbors’ lives. The car free island that can only be reached by boat has been strongly affected by climate change and is expected to dry up completely by the end of the century.

The fate of Gaudí’s native city, too, has always been closely linked with the ocean. To build the Sagrada Familia, he studied the interior of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Mar and visited other historical buildings in the area. On Sunday afternoons, he strolled along the beach to soak up the inspiring shapes of the waves. Nothing in his architecture is straight or edgy – everything seems to flow. The most striking example of this are the serpentine benches at Park Güell. Gaudí‘s Casa Batlló has much in common with Barcelona’s giant aquarium. Ceilings contain whirlpools, facades glitter like the foam of the sea, and the roof resembles a giant reptile. On the coast of Cantabria, for a ship owner who had amassed a fortune in Cuba, Gaudí built the summer house El Capricho featuring a lighthouse. The winery Celler Güell located only 200 m/650 ft from the beach was embedded into the surrounding landscape so smoothly it looks like an upside-down ship.

Wealthy aristocrats like the factory owner Güell loved to surround themselves with artists and poets. Güell, too, had returned from America with considerable wealth, and the combination of his financial muscle and his generosity towards people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds led to a successful cooperation with Gaudí. While the bold architecture graduate had finished his degree with the lowest marks possible, he went on to become one of history’s greatest architects. He could never shake the feeling that he was a failure, and yet, seven of his works ended up becoming world heritage sites. Gaudí’s tendency to combine different styles and create highly individual structures is obvious in all of his projects. It was during his lifetime that History was established as an academic subject, and eclecticism began to flourish. Romanticism had advocated emotional freedom and fostered rejection of rigorous traditions. Ornamental styles developed everywhere in Europe, Catalonia produced Modernism. Gaudí gained new insights studying old buildings, and inspiration from the architecture of Carcassonne, Andalusia, and Morocco. With their floral ornaments and decorative tiles, some of his country mansions and townhouses resemble fairy tale castles taken straight out of the Arabian Nights.

Gaudí’s organic architecture also brought forth a range of new techniques. Paraboloid structures featuring tilted pillars suddenly enabled people to place walls inside rooms wherever they wished. The jewel of his artistic and architectural career is the spiritual forest, a prayer and meditation room inside the Sagrada Familia. The number of visitors his architectural work attracted to the church exceeded all expectations. The wall paintings in Cappadocia’s caves and the Catalonian tradition of building Castellers – human towers – also inspired him. Gaudí’s pillars, vaults, and ceilings resemble tree trunks, branches, and twigs. With technical innovations that made pillars and flying buttresses superfluous, he perfected traditional Gothic architecture.

Gaudí had also studied natural sciences and was adept at botany. It was his closeness to nature that made his style different from Art Nouveau. His ideal structure was an organic, seemingly living body. He always designed structures on site, following a constant spontaneous influx of inspiring moments, they kept them “sprouting” in all kinds of unexpected directions throughout the construction process. Inside the Krypta Güell, which served as an initial source of inspiration for the Sagrada Familia, visitors encounter what seems like a brushwood of pillars taking up the structure of a nearby pine forest. The stairs leading to the entrance were built around an ancient pine tree. The inside of the church resembles a cave made higher by smashing out rocks – another analogy to Defoe’s novel. No pillar resembles the next, like no tree looks exactly like any other. The natural stone façade resembles pine bark. Even the windows imitate specific shapes of nature including flowers, butterfly wings, and spider webs for grilles.

The Sagrada Familia features its own cornucopia of stone flora and fauna. Eighteen different plants can be found on the Portal of Mercy. The vaults inside the church resemble a canopy of leaves, the baldachin brims with grapevines. Various animals grace the Nativity façade, the apse wall seems alive with critters and greenery. Looking at Park Güell, the viaducts resemble the paths nature has built through caves. Gaudí’s Pedrera townhouse with its honeycomb balconies is a sandstone-colored monolithic structure remindful of the Stone Age. Gaudí’s noble goal was to dissolve the boundaries between life, art, and nature.

Trees

A rock by the sea

Hugged tight by a giant root

Of a tall pine tree.

Its branches bending,

Under the ripe load of fruit,

The orange tree abides.

Fairy queen in the

Wind – a slender palm tree on

The white patio.

Behind the old walls

The cypress tree rises like

A gnarled minaret.

Sources: Please see the authors, poet and bibliography in the above link to the online book (imprint at the end of the book)!