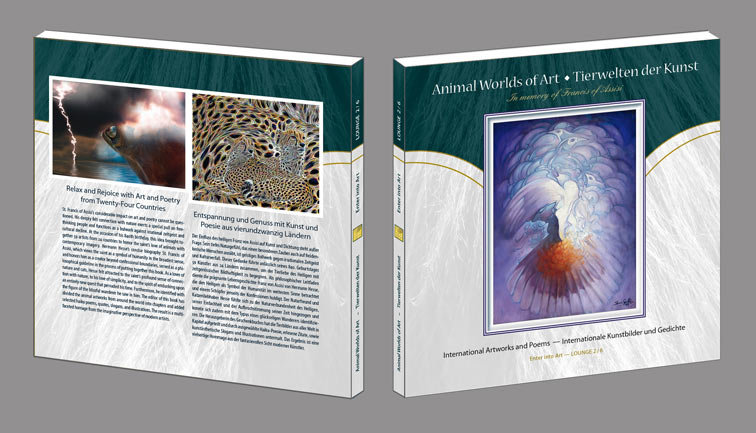

Excerpts from the book “Animal Worlds of Art”

St. Francis of Assisi’s considerable impact on art and poetry cannot be questioned. His deeply felt connection with nature exerts a special pull on free-thinking people and functions as a bulwark against irrational zeitgeist and cultural decline.

At the occasion of his 840th birthday, this idea brought together 60 artists from 24 countries to honor the saint’s love of animals with contemporary imagery. Hermann Hesse’s concise biography St. Francis of Assisi, which views the saint as a symbol of humanity in the broadest sense, and honors him as a creator beyond confessional boundaries, served as a philosophical guideline in the process of putting together this book. As a lover of nature and cats, Hesse felt attracted to the saint’s profound sense of connection with nature, to his love of simplicity, and to the spirit of embarking upon an entirely new quest that pervaded his time. Furthermore, he identified with the figure of the blissful wanderer he saw in him. The editor of this book has divided the animal artworks from around the world into chapters and added selected haiku poems, quotes, slogans, and illustrations. The result is a multifaceted homage from the imaginative perspective of modern artists.

The text and the poems in this post are excerpts from the book “Animal Worlds of Art“.

In Memory of St. Francis of Assisi

Man’s love of animals is reflected in their numerous representations in the visual arts. People with pets smile more often than others. Animals help us communicate positively and be more socially mindful, they build bridges between people, and increase motivation and trust. Their presence alleviates depression and has a positive effect on our health. Especially popular, not only among children and older people, are pets and garden birds. In art books, animal paintings are rare, whereas animal representations in prehistoric caves are part of humanity’s artistic roots. The famous cave paintings of Lascaux still mesmerize people, reverberating like an echo from a time when man used to thank the animals he killed, and ask them for forgiveness. Since animals cannot control their actions, it is up to man to treat them right. The German animal painter Franz Marc has served as a helpful source to me concerning the image of the animal in the arts. In his opinion, what we can learn at the museums is that “no great and pure art can exist without religion”; he also fought for the “animalization of art”. Based on this idea, I have embedded this book in the animal friendly philosophy of St. Francis of Assisi, quite possibly the most popular and likeable of all saints, whose heartfelt relationship with the animal world is the stuff of many legends. Especially the artists and poets of the Renaissance celebrated Saint Francis as a spiritual guide and liberator. Although the itinerant preacher described as a docile rebel and proactive dreamer led a life somewhat removed from reality, he has left behind a humanistic aftereffect spinning invisible threads that remain useful for humanity’s real pursuits unto this day. Their sweetest fruit is art.

Tuning in to the Invisible Spirit of Mother Earth

Franz Marc’s concept of religion follows the tradition of a culture that is thousands of years old. In the Christian frescoes and painting cycles, God’s creation of animals, the animal world in the Garden of Eden, and the animals boarding Noah’s Ark play a major role. In classic mythology, Artemis (Diana to the Romans), the goddess of the hunt, is accompanied by a hind or a stag, a bear, or a boar. The singer Orpheus is portrayed in a circle of animals enchanted by his music. As the holy animal of Athena (Minerva), the owl has become a symbol of scholarship. The Capitoline Wolf and the Egyptian Sphinx are further examples of legendary animal figures. In the masterpieces of Japanese woodblock prints, we find gorgeous representations of birds. The considerably more profane still lifes or hunting scenes of the Old Masters of Europe often have symbolic backgrounds, and certain animals symbolize specific qualities: the horse stands for the dignity of the sovereign, the dog for loyalty, the monkey for vice, the weasel for purity and chastity, the elephant and the lion for strength, the eagle for power.

Goya’s Red Boy depicted playing with a bird and three cats is a touching representation of the relationship between animal and man. Equally famous examples in art history are paintings like Rembrandt’s Elephant, Pieter Bruegel’s Two Chained Monkeys, Albrecht Dürer’s Young Hare, Picasso´s doves and bulls, Rubens’ Lion Hunt, and Leonardo da Vinci`s Leda and the Swan. The Louvre’s exhibit features Giotto’s painting St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, which symbolizes the spirituality of the saint in the form of an intimate conversation with nature. While hunting birds was a popular pastime among the nobility, St. Francis lovingly saw them as his feathered brothers and sisters. Like St. Francis, Giotto, too, adopted the habit of directly observing nature, thus laying the groundwork for the great Tuscan art that heralded the birth of the Renaissance.

A fresco he painted in the upper church of the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi also shows the saint preaching to the birds at Bevagna (around 1295). The two frescoes left and right of the church portal (The Miracle of the Spring and The Sermon of the Birds) embody the lyrical aspect of his famous St. Francis Cycle. Of great art-historical importance, this cycle of frescoes depicts 28 anecdotes from the life of St. Francis of Assisi and was aimed at spreading the saint’s core message. The gothic rose window above the church portal allows the light to shine down from the sky– the colorful glass windows of the church are among Italy’s most stunning – next, visitors step into radiant blue and discover the Umbrian Garden of Eden. The Rieti Valley is one of the most beautiful landscapes of Europe. St. Francis’ Paradise on Earth was where we like to spend our holidays today, or embark on informative cultural study trips. Among birdsong, a dozen hermitages still tell us that, for a while, this area in central Italy was something of a new Galilee, where St. Francis, like Jesus before him, told the people about God’s kingdom of peace.

About 2,5 miles from Assisi stands the Portiuncula Chapel, which is among the churches St. Francis is said to have restored and renovated with his own hands. This is where, legend has it, the founder of the monastic order died on the bare floor. As head of the order, he had already stepped down during his lifetime. The large plaza brimming with greenery is remindful of the ancient oak wood that once surrounded the small church. Today, the huge Baroque Basilica Santa Maria degli Angeli Assisi encloses the former forest chapel. The different shapes of the nested architectural structures emphasize the discrepancy between the church as an institution and the persona of St. Francis of Assisi. The “Long Well” on the shady north side reminds visitors of the miracle of the spring. It was donated by the Medici family to quench pilgrims’ thirst with its 26 water fountains. From the right transept visitors can enter a rose garden whose roses – legend has it – lost their thorns after the Saint had engaged in an intense exercise of penance.

Few other saints have been depicted so frequently in the context of the legends associated with them. Hermann Hesse was not the only one deeply touched by the popular Little Flowers of St. Francis (Fioretti) featuring the most beautiful stories of the saint’s love of nature and animals resulting in a profound humanist dimension. Illuminated by the lyrical light of world literature remindful of the sublime sparkle of precious icons, it is a collection of stories told by the people for the people. Again and again, they reveal the saint’s message to respect animals as free beings and liberate them from captivity. Animals are intentionally addressed as respectable brothers. St. Francis was fundamentally opposed to taking animals prisoners and view them as possessions, rejecting any form of appropriation as an original human sin. The reason these legends are so poetic is the fact that they are not about keeping animals.

St. Francis would have liked an imperial edict to be issued against capturing and killing songbirds – but not even this wish was granted to him… He built nests for them, they alighted on his shoulders and ate out of his hand. He preferred the larks to the kings’ and emperors’ heraldic animals. He loved listening to the crickets chirping in the fig tree and, like a troubadour, sang along with the nightingale whenever it performed its jubilant song. He loved the crested lark because it wore a hood and the colors of the earth, just like a barefooted monk. In his barefoot movement, St. Francis sought contact with the humus of the earth, like an old cat that, after spending years in a human home, goes to find its final resting place outside and refuses to come back in – returning to primal wilderness and Mother Earth. St. Francis picked up worms from the path to carry them into safety. A pheasant he released ended up following his every step. He comforted the lambs to be slaughtered and cared for the bees in the winter. When a wolf started killing animals, terrorizing people and animals in the town of Gubbio, St. Francis convinced him to stop, negotiating a kind of peace treaty between man and animal remindful of an economic solidarity pact that made the evil enemy’s destructive fury evaporate.

St. Francis of Assisi had to return home sick from his time as a prisoner of war before he was able to embark on a new life of asceticism. Spending time at different hermitages, he saw with his own eyes how animals led a life in sync with their environment. Tuned in to the heartbeat of nature, they can feel the movement of the sun and the moon, the seasons, the tide, and even the pending arrival of natural disasters. Creatively and organically, they incorporate their homes into their environment. They have a fine sense of smell and know the right time to fly to a warmer place. They take no more and no less than what they need! This may have inspired St. Francis to emulate their ways and in turn, inspire others to think about their ways through his own exceptionally mindful way of life. St. Francis of Assisi was not a revolutionary, but a peaceful reformer who inspired new ways of thinking and shook up the old. The only nobility he worshipped was the nobility of the heart.

Wilderness

A chattering swarm

In the blue sky, the wild geese

Are flying souththward.

At the edge of the

Meadow, deer grazing among

The sloes’ dreamy scent.

Bats dancing inside

The ruins. The horizon

Ablaze with lightning.

In the gray sky, black

And serene, the buzzard

Circles, drifs, stills, and turns.

Sources: Please see the authors, poet and bibliography in the above link to the online book (imprint at the end of the book)!