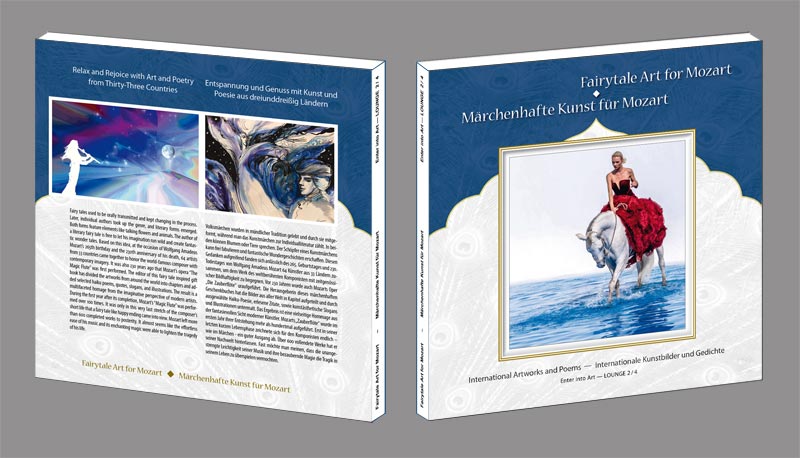

Excerpts from the book “Fairytale Art for Mozart”

Apparently, Mozart’s pet songbird could whistle a few bars of his piano concert in G major (K. 453). Did Mozart live in a magic world we love to hear stories about, even if we find them unbelievable? The prelude to his marriage, too, resembles a love story with obstacles the couple had to overcome to be united. Father Leopold was exasperated when Mozart decided to leave Salzburg and embark on the insecure life of a freelancer. Also, he did not approve of his son’s wife Constanze. Maybe this was why Wolfgang hardly mentioned his father’s passing in 1787, while dedicating a long obituary to his “star songbird”, which died around the same time. If we try to judge Mozart’s life in the simplistic terms of fairy tales, based on our conventional ideas of “good” and “bad”, we inevitably encounter contradictions.

Like many fairy tales, the “Magic Flute” has two parts. Its heroes wear fantastic feathered costumes and face difficulties they have to overcome or be saved from. Finally, the objects of their longing are manifested in a happy ending. In fairy tales, too, paradoxes are so common they hardly even appear as such. Clearly divided into good and bad at first, in the second part, the world of “The Magic Flute” suddenly turns upside down. Who is good, and who is bad now? Maybe, this was the reason the first performance conducted by Mozart himself was not a great success. The brilliant melodies and fairy tale imagery, however, were as memorable then as they are today. Like the artworks and poems in this book, fairy tales are marked by stylistic integrity and poetic effect. Time and again, “The Magic Flute” has inspired visual artists like Oskar Kokoschka or Karl Friedrich Schinkel with his 12 orientally inspired stage sets.

The text and the poems in this post are excerpts from the book “Fairytale Art for Mozart“.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – A genius that remained unrecognized throughout his lifetime

Due to their power to transform bad into good, fairy tales are morally satisfying. This amazing power, however, tends to be limited to fairyland. While the opposing forces of reality and fantasy did play a part in the life of the child prodigy Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791), the miracle of salvation did not manifest for the brilliant composer towards the end of his life. Instead, biographical records suggest intrigues, and as opposed to most fairy tale protagonists, he was not magically saved from them. As outstanding as his talent was, and as much as people craved his compositions, they never seemed to think of paying or supporting him adequately. Today, a single work like “A Little Night Music“ would have earned him enough for a lifetime. Instead, at one point, he was forced to sell his horse because he needed the 14 ducats. Even in his heyday, his pay barely amounted to half of what composers like Antonio Salieri or Joseph Haydn made. Finally, he decided to move to England. In his letters to Constanze, however, he talks about “fatal situations“ and “unforeseen coincidences”. Mozart died unexpectedly at the age of 36 – only a few weeks after “The Magic Flute’s” first performance, and while he was still working on the requiem commissioned by an impatient man who did not reveal his identity to him. The cause of his death remains unknown. When they lowered Mozart’s slight body into a paltry grave on 6 December 1791, nobody realized what a gifted genius was being buried in front of them. Throughout his life, the people of Vienna had shunned his divine music.

But why did Mozart’s upper-class friends and the nobility turn away from him? Even the priest refused to pay a visit at his deathbed – possibly because Mozart was known to be a Freemason, and a “renegade”. In fact, authority and arrogance were alien to him, and he was indifferent to nobility, courtly splendor, and medals. According to his contemporary Franz Xavier Niemetschek, Vienna only seemed to wait for the inconvenient person he was “to acquire greatness in death, as his transcendence shifted from negative to positive”. As a friend of the family, Niemetschek describes Mozart as a friendly and unselfish person who “lived completely in the world of musical notes” and often worked without pay, or for charity. He frequently fell victim to his good-natured trust in others. Mozart lived humanity and tolerance. Many of those around him, however, did not appreciate his lack of diplomatic skill and his amused aura.

Where do we find ourselves? Is this an incomplete jigsaw puzzle of the unspeakable, or is it the world of drama and legend? Did the composer fall victim to envious defamation and cabals in a fight between spitefulness and the nature of art? Undoubtedly, Mozart was an artist who valued his independence and did not necessarily see art as something “useful”. To the naturally gifted Mozart, apart from perfection, the muse embodied freedom and inspiration, and was more likely to favor children than calculating adults. According to his sister Nannerl, Mozart himself remained a child until he died, except when it came to music. People found petty faults in him like chaoticism and wastefulness. But is it not precisely the spontaneity of “letting oneself go” that leads to great art? Is it our right to be so selfish and expect from a genius to be a role model in every aspect of life? Mozart especially suffered from people hurting his honor and his pride as a musician. Certainly, as a child prodigy, he was born with music in his veins, so his spirit could playfully soar to the highest spheres of artistic achievement. The most wonderful melodies poured from his fingers – as a musician, he was all emotion and euphony. He started touring Europe as child, later he temporarily lived in Paris. Leopold Mozart organized concerts for his son at all the important opera houses of Italy, they would spend several weeks at a time in Venice. Wolfgang understood French, English, Italian, and German, and knew the writers of the nations. Quite possibly, he had also read the French orientalist Antoine Galland’s successful translation of “One Thousand and One Nights”.

While only some of the tales in it may be classified as fairy tales, “One Thousand and One Nights” is a literary creation that offers a framework of fantastic stories with opulent appeal, unfolding devotedly and sensuously like fragrant flowers – which Mozart loved. Oriental fairy tales and exoticism were greatly en vogue during the rococo era. The time’s fervent borrowings from Turkish culture led to a fantastic parallel world open to dreamy projections, allowing people to be enchanted by the unknown. Not only “The Magic Flute” shows the fairy tale like orientalism of Mozart’s work. The musical comedy “Abduction from the Seraglio” also features the saber rattling of the janissaries. In violin concerto no. 5 in A major, KV 219, and in the “Alla Turca” part of the piano sonata in A major, KV 331, the marching character of the music mimics their stride. In “The Magic Flute”, oriental mythology appears in the form of the ancient gods Isis and Osiris. The center of the action is an Egyptian sun temple ruled by a wise priest. The opera was based on different oriental fairy tales and fables, as well as Jean Terrasson’s novel “Life of Sethos” and the story of the Egyptian king told it tells.

A lot of “The Magic Flute’s” elements are remindful of fairy tales: The Queen of the Night gives Tamino a golden flute he can immediately play. We encounter golden palm fronds and a waterfall in a silver forest. Pamina is abducted by a “moor” and taken to an oriental abode. Also, throughout the work, the composer frequently employs the magic number three. The overture starts with three chords, right in the beginning, three ladies sing an exquisite trio, later three boys appear, and finally, Tamino has to undergo three ordeals. Overall, “The Magic Flute” is an ode to the Three Pillars of Freemasonry: Strength, Beauty, and Wisdom. Even the dominant key of the work has three flats. And what could be more fairy tale-like and enchanting than bird catcher Papageno’s duet with his sweetheart Papagena, which played a crucial role in the work’s popularization? Mozart urgently needed money and, through the transformative power of his magic music, he turned Emanuel Schikaneder’s light libretto into a world success.

Night Music

Off to a concert

In the river valley,

A date with the thrushes.

Bubbling fountains and

Gentle reveries rising

Up in moonlit spray.

The male nightingale

Serenading at night like

A true troubadour.

Suddenly the scent

Of jasmine in the moonlit

Breeze of the warm night.

Sources: Please see the authors, poet and bibliography in the above link to the online book (imprint at the end of the book)!