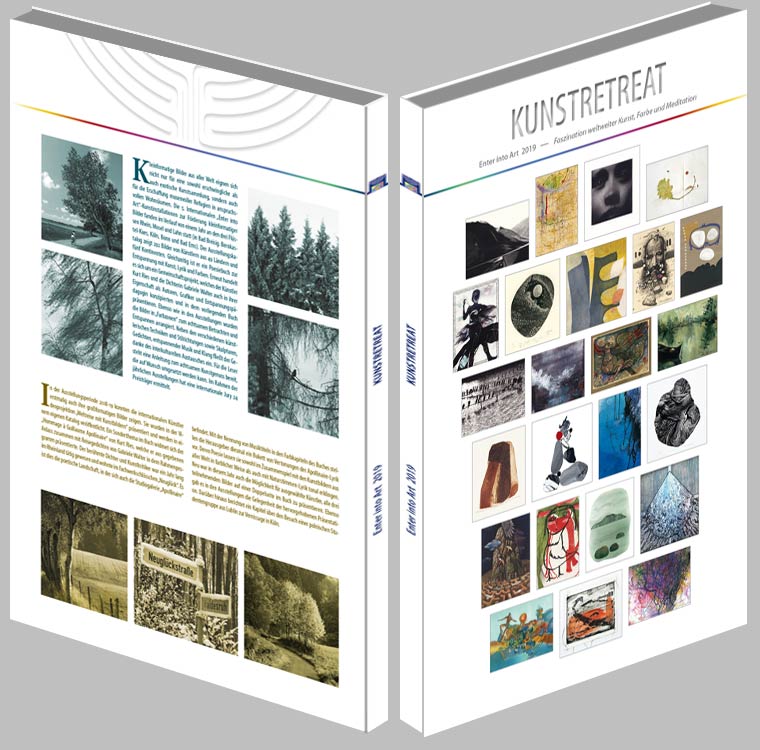

Excerpt from the book “Art Retreat 2019”

Apollinaire and Music

As it seemed fitting, we decided to return to the theme of our “Hommage à Guillaume Apollinaire“ during the exhibition period of 2018-2019. This time, we are honoring the great French poet with our latest book. Each chapter is dedicated to a color and begins with the name of a composer followed by a piece of music set by the same to one of Apollinaire’s poems. This is yet another way to continue our tradition of bringing together visual arts with poetry and music in our events and art books. Doubtlessly, our artistic creativity also draws on the poetic soulscape inhabited by the famous poet, art critic, and friend of Picasso’s for an entire year.

Studio Gallery “Apollinaire”

It was Guillaume Apollinaire’s stay only a stone’s throw away from here that inspired us to name our studio gallery in Bonn-Königswinter after the famous poet (2018 saw the 100th anniversary of his death). Emulating Apollinaire’s inventive avantgarde mind, “Apollinaire” Studio Gallery follows a novel concept giving artists from around the world a unique platform to present themselves. In the context of our international competition series “Enter into Art”, it will serve as a reputable stage to innovative art shows and art book presentations in the future. Only a short “Sunday walk” away stands the half-timbered castle Neuglück where Apollinaire worked as a private tutor to a family of Francophile aristocrats between August 1901 and August 1902.

The text and the poems in this post are excerpts from the book “Kunstretreat” 2019, vol. 5“.

Apollinaire’s stay in Germany was a stroke of luck for the history of literature. Getting paid in advance, he could take in the poetic scenery around him at his leisure and make it his own through songs and poems. The writing he produced during this time is lasting proof of how important it is to promote the arts by providing appropriate social settings! Later in his life, Apollinaire returned to the Rhineland once again. Together with artist Robert Delaunay, he visited August Macke in Bonn, where he met the young Max Ernst. He kept his distance from Germany after 1914, which is only understandable.

But how exactly does the “genius loci” of our area manifest itself in his work? Apollinaire was 21 when he stayed in Germany. This was before he became part of the literary bohemia at Montmartre and mingled with people like Picasso, Braque, Gris, Léger, and Marcel Duchamp. With a series of accomplished poems in his pocket, he returned from Germany to Paris where he dedicated himself to publishing his work, and building a successful career as a poet. The Rhine poems mark a first poetic climax of his work. Although he had written poems before this time, his stay at Neuglück was the true starting point of his career as a poet.

The Young Poet at Neuglück Castle

Doubtlessly, the “Rhénane” and Apollinaire’s other later poems, too, were strongly influenced by the impressions he gleaned from this area. This became the subject of academic research in Ernst Wolf’s dissertation “Guillaume Apollinaire und das Rheinland“ (“Guillaume Apollinaire and the Rhineland” – Shortly after its publication in 1937, the author was forced to emigrate to Sweden/ the United States.) Especially the scenery around Neuglück Castle was both new and fascinating to the young poet. Back then, the elegant half-timbered castle set on top of a hill was the only building far and wide. The deep coniferous forest depicted in Apollinaire’s poem “Les Sapins” (“Fir Trees”) still exists today. We can assume that before he came to Germany, the only geographic settings familiar to the young poet had been Mediterranean landscapes and the city of Paris he had hardly left.

The wind, the fir trees, the triad of garden, forest, and fields, the sunsets from up here, the elegant half-timber construction, and his first love – the entire pastoral surroundings of Neuglück with their northern mood keep reappearing throughout Apollinaire’s work. Fall was his favorite season, and in this area, fall is magnificent. This, too, influenced his creative work. Most of the poems he wrote in the Rhineland were composed in the fall of 1901: The stormy season with its dying nature became the epitome of death in Apollinaire’s poetic landscape. It is highly probable that Neuglück also served as a setting for the poems “Passion“ and “Le Vent Nocturne“ (Night Wind). “Automne“ (“Aurumn”), “Les Colchique“ (“Autumn Crocuses”), and „L‘Automne malade“ (“Autumn Ill”) also prominently feature the season.

It was during his stay in Germany that young Apollinaire first discovered folk songs. A German folk song is sung in his poem “Nuit Rhénane“ (“Rhine Night”). In what may be his most important poem – “La Chanson du Mal-Aimé” (“Song of the Poorly Loved”) – he mentions the Rhineland winter and his love for the English woman Annie Playden who was working as a governess at Neuglück while he was staying there. She was his first love. He went to see her in London later, but eventually, Annie Playden emigrated to America. The experience of failed love also played a part in shaping the depiction of our local scenery in his work, giving it a sentimental touch, and turning it into a melancholy soulscape.

The romantic castles and ruins of the actual Rhineland, on the other hand, appear only marginally in Apollinaire’s lyrical imagery. In a letter to his mother, he compares the vineyards in the nearby Rhine Valley with the Mediterranean Riviera of his childhood. Legend has it that the poet met his lover in the midst of this lyrical landscape, at Bahnhof Rolandseck, where the Arp-Musem is located today. The nearby island of Nonnenwerth was once home to the composer Franz Lisz, and Beethoven was born in the Rhenish city of Bonn. This is also the landscape of William Turner, Heinrich Heine, and Lord Byron. Although Apollinaire always remained fond of the south, the northern scenery around Neuglück also inspired him greatly.

Aesthetic Observations

Apollinaire‘s stay in our area, however, was only one of several factors that motivated us to make his artistic views the conceptual foundation of our projects. Just like the famous poet, we cultivate a connection between contemporary art and meditative observation, poetry, and sound, because each color is a tone contributing to the completion of harmony. The same is true for poetry. The picturesque Rhineland inspired Apollinaire to compose some of the most melodious verses in French literature. Just like the haiku poets, he found a lot of his poetic impulses while hiking through nature, and the seasons feature prominently in his poetry. The two opposing landscapes right here at our doorstep are also a continuous source of inspiration to Gabriele Walter, and continuously prompt her to write new haiku poems. We are happy to include them in our group projects and keep building upon the poetic flair of our surroundings.

It was also in Germany that Apollinaire wrote his first art reviews. Being a proponent of free verse and modern painting, even his reviews resembled melodious sonnets. At the same time, his observations on art have inspired us to make our own, and, like him, give artists the opportunity to present themselves in a unique way (also see: “Featured Artist”). In his book “The Cubist Painters – Aesthetic Meditations” he coined the term “Orphism”. After staying with Robert Delaunay for a while, he drew parallels between Delaunay’s abstract art and music.

What Rainer Maria Rilke is to the Germans, Guillaume Apollinaire with his linguistic brilliance and musicality is to the French. No matter what part you look at, his verses can be enjoyed like pleasant little tunes, his works offer a unique sense of linguistic ecstasy. In one of his verses, Apollinaire compares the rustling of the wind with the sound of an organ. Not only in the context of Dadaism does Apollinaire’s poetic form appear as a musical composition of sounds, colors, and mental rhythms comparable to the poetic work of Hans Arp.

Apollinaire’s Poems Set to Music

Although Apollinaire has left us little on how he felt about the subject of music, and believed himself to lack musicality, we want to pursue the question of his musicality a little further. In this context, it seems useful to look at the review he wrote about the premiere of Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau’s ballet “Parade” in 1917 for which Picasso had designed the stage set. Apollinaire hailed Satie as an avantgarde artist and lists Stravinsky as one of several Futurist artists. In his aesthetic observations, he talks about color and rhythm mutually influencing each other.

Much more important than his comments on music, however, is the fact that his poetry has inspired more than 40 different composers. The epoch-making success and musicality of his poems is reflected in the music many famous composers have written to them. Apollinaire’s later work mainly inspired traditional composers, as his poetry did contain traditional elements. On the other hand, two characteristic features of his more modern poetry have inspired composers: its musicality and the sound of its language.

The Swiss composer Arthur Honegger was the first person to set Apollinaire’s writing to music. It is possible that the poet knew of and heard these compositions. For his “Six poémes” for vocals and piano written between 1915 and 1917, he chose poems from the “Alcools”. Dimitri Schostakovitsch set several parts of his 14th symphony, which centered on the subjects of death and parting to Apollinaire’s words, translated into and sung in Russian. Several composers including Léo Ferré, Daniel Ruyneman, Jean Absil, Louis Beydts, Lionel Daumis, Jacques Lasry, and Jean Rivier were inspired by the poem “Le point Mirabeau”, resulting in as many musical versions of it.

When Francis Poulence heard the poet recite his own work at various occasions, he was taken with his musicality and mode of presentation. He was overjoyed when Apollinaire’s friend Marie Laurencin thought she could hear the poet’s voice in Poulenc’s songs. Poulenc dedicated a lot of attention to the musicality of language and saw himself as a musician inspired by “Apollinaire and Eluard”. His cycle “Caligrammes” written in 1948 was based on seven poems from Apollinaire’s poetry collection of the same name. Chansonniers like Marcel Mouloudji and Léo Ferré were also among those who sang Apollinaire’s poems. Our own selection of music set to Apollinaire’s words was determined by our wish to establish a connection with the Rhineland and the homage put together by Kurt Ries.

His “Hommage à Guillaume Apollinaire“ was shown in Cologne, Bad Breisig, and Bernkastel-Kues in the context of our video projection “Touring the World through Art“, and presented anew in combination with 24 traveling haiku written by Gabriele Walter. Our exhibition space enabled us to add this as a bonus event to our “5th International Enter-into-Art Installation” featuring small paintings. This gave the participating artists from around the world a chance to present paintings in larger formats, too. The pictures from the video projection and the traveling poems will be published in the art book “A Fine Art Journey”.

Art Meditation

Imagine you are at an exhibition featuring the works in the book, mindfully observing them. Close your eyes and observe your breath, or listen to it, until you feel pleasantly calm. Pick a painting:

- What is this artwork about? What is special about it?

- Take your time and analyze the colors and shapes in this work. Feel their sound!

- What spontaneous associations does this artwork trigger in you?

- What would you say is “that certain something” about it – that mysterious aspect that is difficult put into words, and that has sprung directly from the artist’s soul?

Haiku Featuring the Voices of Birds and Nature

Music of the Universe

Just like poetry lends itself to song, music also lends itself to poetic expression. After all, both language and music are products of nature. Virtuoso voices, thumping or hypnotic basic rhythms, enraptured trills, refreshing swirls, dances, and dialogues, quiet arias, and sweet melodies marked by poetic beauty are themes not only found in nature but also in orchestral music. In tune with our Apollinaire theme, the poems in this book poetically reproduce the musical sounds of nature. Listen to a concert played by the universe itself as you read these haiku!

Nocturnal birds dance

A strange gymnopedia

Down by the field pond.

The blue tit chatters

All the way from the quince to

The blossoming pear.

Bubbling and gurgling

Fresh melodies in the mist:

White winter-time creek.

Seagulls’ joyful screams

Red gold hits the ocean’s face

The kiss of sunrise.

The quiet chatter

Of the last leaves clinging to

The big linden tree.

Rhythmically the birds

Under the wisteria

Rock themselves to sleep.

Sources: Please see the authors, poet and bibliography in the above link to the online book (imprint at the end of the book)!